A Bisl Torah — Help it Grow

May it be a season of change and a season of growth.

May it be a season of change and a season of growth.

The post A Bisl Torah — Help it Grow appeared first on Jewish Journal.

May it be a season of change and a season of growth.

May it be a season of change and a season of growth.

The post A Bisl Torah — Help it Grow appeared first on Jewish Journal.

[…]

[…]

The post Hermeneutics of Suspicion Casting Suspicion appeared first on Jewish Journal.

JFSLA’s Community Impact Network aims to inspire and equip young adults to lead social change

JFSLA’s Community Impact Network aims to inspire and equip young adults to lead social change

The post Jewish Family Service LA Launches Program to Shape Next Generation of Social Service Leaders appeared first on Jewish Journal.

Law enforcement vehicles sit parked outside a reported residence of a suspect following a mass shooting at Annunciation Catholic School on Aug. 27, 2025 in Richfield, Minnesota. / Credit: Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

Law enforcement vehicles sit parked outside a reported residence of a suspect following a mass shooting at Annunciation Catholic School on Aug. 27, 2025 in Richfield, Minnesota. / Credit: Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

Washington, D.C. Newsroom, Aug 27, 2025 / 20:15 pm (CNA).

The man who killed two children and injured 17 other people in the Minneapolis Catholic church shooting posted a YouTube video before the attack, which showed an anti-Christian motivation for the murders and an affinity for mass shooters, Satanism, antisemitism, and racism.

Robin Westman — who was born “Robert” and identified as a transgender woman — died by suicide on Wednesday, Aug. 27, after shooting through the windows of Annunciation Catholic Church during a weekday Mass. Most of the worshippers were children who attend the parish elementary school next to the church.

In a video posted ahead of the attack, which YouTube has since removed from its website, the shooter showed a written apology to his friends and family but clarified “that’s the only people I’m sorry to” and then disparaged the children he planned to shoot.

Westman wrote that he has “wanted this for so long” and acknowledged: “I’m not well. I’m not right. I am a sad person, haunted by these thoughts that do not go away. I know this is wrong, but I can’t seem to stop myself.”

During the video, Westman zooms in on an image of Jesus Christ wearing the crown of thorns that he attached to the head of a human-shaped shooting target. The photo of Christ displayed the text “He came to pay a debt he didn’t owe because we owe a debt we cannot repay” below the image.

Westman laughed while pointing the camera at the shooting target, and then moved the camera to show anti-Christian messages and drawings on his guns and loaded magazines.

One message read: “Where’s your God?” and another: “Where’s your [expletive] God now?” A third read: “Do you believe in God?” while another stated “[expletive] everything you stand for.”

Another message on a rifle stated “take this all of you and eat,” which mocks the words Jesus Christ said at the Last Supper and the words said in the Eucharistic prayer during every Mass.

Westman drew an inverted pentagram on one of the magazines, which is a symbol often used to promote Satanism but is sometimes used in other occult practices. The number “666” was also written on the magazine. He also drew an inverted cross on the barrel of one of the rifles, which is a traditional Christian symbol that has since been co-opted by Satanists.

Westman wrote the names of about a dozen mass murderers on his weapons. Most of the names were written on magazines, while some were written on the rifles.

One mass murderer that Westman referenced multiple times on magazines and rifles was the Norwegian neo-Nazi Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people and injured 319 others in two mass casualty attacks.

He also referenced the New Zealand Christchurch mosque shooter Brenton Harrison Tarrant, the Abundant Life Christian School shooter Natalie Rupnow, the Sandy Hook shooter Adam Lanza, and the Aurora Night Club shooter James Holmes.

Several written messages were antisemitic, such as “6 million wasn’t enough,” in reference to the number of Jewish people killed during the Holocaust. A smoke grenade he showed had “Jew gas” written on it, which is another Holocaust reference. There were also several anti-Israel messages.

Other messages targeted several ethnic and racial groups. One message used a slur for Hispanic people and another said “Nuke India.” One message read “remove kebab,” which is a reference to a meme disparaging Arab and Muslim people. Another written message referenced a meme mocking Black people.

Several messages also disparaged and threatened to kill President Donald Trump.

One message on a loaded magazine read “for the kids” and another read Mashallah, which is Arabic for “God has willed it.” Others referenced various memes and two of them referenced the movie “Joker.”

In his video, Westman flashed the “OK” hand symbol one time when showing his weapons. This appeared to be a reference to the Abundant Life Christian School shooter, Rupnow, who posted an image of herself displaying the same symbol before her attack.

Although use of the “OK” hand symbol is usually benign, it has also been used by some white supremacists as a sign of their ideology.

Researchers who tracked Rupnow’s social media activity found that the 15-year-old shooter was deeply involved in online networks that espouse neo-Nazi, racist, and Satanic beliefs, according to a joint report from Wisconsin Watch and ProPublica. The communities also promote violence and some have praised mass shootings.

Although Westman referenced Rupnow and used rhetoric promoting both Satanism and neo-Nazi ideology, so far there is no direct evidence that connects Westman to these communities.

(RNS) — After years of working for a Christian international relief group, sociologist and professor Kurt Ver Beek wasn’t satisfied with the tool kit available to most faith groups combating poverty. To him, mission trips, direct aid and even strategies like micro loans largely seemed aimed at targeting the symptoms of poverty, rather than its root causes.

In 1998, Ver Beek and his wife, Jo Ann Van Engen, became co-founders of La Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (in English, the Association for a More Just Society). Based in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, the Christian nonprofit sought to understand and then dismantle the systemic barriers preventing communities in Honduras from thriving — namely gang violence, police corruption and government mismanagement.

Over the past several decades, that’s involved hiring investigators to track down gang leaders on a murder spree, working with mental health professionals to address the factors causing youths to join gangs in the first place, partnering with national religious leaders and top government officials to purge the national police force of corruption, and conducting and publishing audits on everything from the annual number of school days to how government programs used emergency funds.

In May, a new book, “Bear Witness: The Pursuit of Justice in a Violent Land,” documented the efforts of Ver Beek, his Honduran co-leader Carlos Hernández and the rest of the ASJ team as they applied their approach to risky, morally complex and highly impactful endeavors. RNS spoke to Ver Beek about the faith that’s shaped his work, how ASJ has navigated ethical dilemmas and why other nonprofits should take anti-violence work seriously. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The book was written by an independent journalist, so we didn’t see any version until it was finished. In the end, we feel like he got, I would say, 90% right. I think he, for the purpose of the story, made it all about Carlos and I, but there’s a ton of other people. When we were purging the police, which was a very huge and scary thing, that decision was made with the head of the Protestant church and the head of the Catholic Church and the National University president. If and when there were missteps, others were involved in those decisions. There were a few negative pieces to the book, but mostly it was very positive reading about it 20 years later.

The Christian Reformed Church is of the Calvinist tradition, which teaches that we are called to transform this world. There’s a Calvinist theologian named Abraham Kuyper who said we are called to transform every square inch of this world, and that we are God’s agents of change. Being brought up in that church and shaped by education in that church is really part of my religious DNA.

Parts of that were hard on me, probably even harder on Carlos. Carlos ran schools and summer camps in our neighborhood. One of the kids who was the most violent, who probably killed 15 to 20 people that we know of, went to one of the summer camps. He was a smart kid. Really rough family, but he was leading a gang, and was clearly the most violent member. If there’s a gang of 40, 50 kids, it’s often one or two of them that seem to enjoy it, and the rest of them follow along. So it wasn’t that hard to do what we did. If you can pull one or two people out of that group, the gang doesn’t disappear, but the violence often drops dramatically. Those were the people we were focusing on, which meant saving a bunch of other lives.

We would often talk to their moms and aunts, and they would say, he’s going to either end up in jail, or dead in the gutter somewhere, and we’d rather he was in jail. Maybe God can turn his life around. One thing we also did was to try and start a program, which is still going, for the most at-risk youth in our neighborhoods, trying to catch these kids before they got in. We’d start with kids ages 10 to 11 from those same sorts of families. For a while, we were also trying to fix up the juvenile detention center. It became problematic because we were putting kids in there, and we eventually had to stop doing that because of conflicts of interest. But we were very aware that this was not a good place for these kids, and we were trying to keep them from going down this path. We have gone back into trying to work in juvenile centers for the last four or five years, to try to make it safer.

I don’t know to what extent I would universalize it, but from everything I know, I would be very tempted. When it comes to poverty, violence is still not a common issue addressed. One of the main reasons is that addressing this violence issue puts aid workers and their staff at risk. When you live with the people that you’re serving, you end up figuring out that those problems they’re addressing every day are much more complicated than you thought.

We had a woman in our neighborhood we were helping, giving her a loan to start a pillow business. Within months she had four employees, making all these pillows. And then the gang showed up. Within a month or two, they were extorting her for more than what her profits were, and threatening her and her daughter. And she just closed the shop.

In Honduras, there’s hundreds of micro enterprise organizations that are giving out millions of dollars a year. And lots of donors in the U.S. love it. But I don’t know of any other Christian organization working on violence in those same neighborhoods. I think we’re the only one. So you just see the mismatch there. It isn’t that people should stop doing micro enterprise. But I think they only address a part, and they often miss the base things people need to make that business work.

I used to be very critical of the church, as a young person. I was idealistic, and didn’t see that the church was living out Jesus, especially the way I understood Jesus, as fighting for the poor and the vulnerable. And I think all this experience, with the police purge, the Protestant pastors were the powerhouse behind that. I’ve seen people of all sorts of faiths being brave. So I’m way less critical. If it’s the body of Christ, we have different callings and gifts. I have just one of those callings. So I’m more humble. I think I probably had a more individualistic idea of salvation and faith that has become more communal. And there’s a lot of discussion now about empire. I’m not a theologian, but there’s something there that makes sense to me, that we are fighting systems.

The church I see right now, in the Christian Reformed Church in North America, is not a place I feel very comfortable. I think the teachings, the base theology, is all still there, but it’s become completely polarized over LGBTQ, and around a whole bunch of other issues, even women in office. One side of the church is trying to impose its will on the other, and felt, I think, to some extent, like the other side imposed their will on them years ago. It mirrors politics in the U.S. right now. It’s a very divided church. Lots of people are leaving. Many young people don’t want to go to that church. It’s a rough time in the denomination. Jo Ann and I being in Honduras, it makes us sad to see all this happening. I still resonate strongly with this idea that we are called to be agents of transformation of every square inch. But I’m very saddened by all of the inciting polarization now, which is happening in lots of other churches, too.

(RNS) — When an impoverished neighborhood’s biggest obstacle is its murder rate, no amount of food donations and micro-loans will alleviate suffering.

Sociologist Kurt Ver Beek knows this firsthand. That’s why, when the struggling Honduran neighborhood of Nueva Suyapa was overrun by a murderous teen gang in the mid-aughts, the Honduras-based organization Ver Beek co-founded, La Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (in English, the Association for a More Just Society), made radical moves outside the typical Christian nonprofit playbook. The top priority became anti-violence work: supporting victims, equipping police to prosecute crimes and addressing the systemic factors pressuring youths to join gangs in the first place.

The impact was staggering. Homicides in Nueva Suyapa dropped by roughly 75% between 2005 and 2009, a period coinciding with ASJ’s community interventions, according to the organization.

“When it comes to poverty, violence is still not a common issue addressed,” said Ver Beek, who believes that while aid and development work are important, they stop short of addressing root causes of injustice.

Despite the radical impact, ASJ, then a fledgling organization, had largely operated under the radar in Honduras until 2016, when ASJ was invited by Honduras’ president to serve on a commission to purge the National Police Force of corruption. As ASJ became recognized on the national stage, it caught the attention of journalist Ross Halperin, whose book about ASJ, “Bear Witness: The Pursuit of Justice in a Violent Land,” was published in May. And in recent years, ASJ has also shaped the methods of nonprofits in other locations grappling with violence and police corruption — including Chicago.

“We have, in some respects, many of the same problems that they have,” said longtime Chicago-based nonprofit leader Joel Hamernick. “The systems work differently, but I think that that model can be brought to bear here.”

As nonprofits in Chicago ponder how to implement the ASJ approach, Ver Beek knows they’ll face the same questions ASJ has been wrestling with for decades: What is justice, really? Who are you willing to partner with to achieve it? And what, if anything, does faith have to do with it?

Christianity has always been central to the ASJ mission. Ver Beek and his wife, Jo Ann Van Engen, are graduates of a college affiliated with the Christian Reformed Church in North America, a small, Protestant denomination founded by Dutch immigrants. In 1988, the couple went to Tegucigalpa, Honduras, as employees of the denomination’s international relief arm. A decade later, they founded ASJ as a Christian organization addressing injustice on a deeper, systemic level.

“It’s just part of my faith that I don’t even think about,” Ver Beek told RNS. “Of course we should be doing justice. Of course, if our neighbors are hurting, we don’t just evangelize them; we have to figure out what we can do to help.”

But while Ver Beek told RNS he sees faith as fueling ASJ’s passion for change, he’s under no illusion that Christian nonprofits are more successful than secular ones. The key to ASJ’s impact, Ver Beek argues, is its four-part strategy: researching problems to understand them; building alliances with influential partners; communicating about these efforts with the public and the media; and lobbying decision-makers to make informed changes.

That first step, he says, is one many nonprofits skip.

“They jump in to try and fix things,” said Ver Beek. “They think they understand things, especially they think we understand the life of poor people, what they need, how they need it.”

ASJ has employed this four-part method to tackle challenges across multiple sectors. In 2013, an ASJ-led campaign helped to see the average number of school days in Honduras jump from 125 to over 200. From 2016-2019, ASJ partnered with religious and government leaders to purge the police force of corruption, terminating 42% of police evaluated (5,775 individuals). According to Ver Beek, this contributed to a drop in the entire country’s homicide rate, from 90 murders per 100,000 people in 2012 to 22 murders per 100,000 people in 2024. During the COVID-19 pandemic, an ASJ audit of $80 million in government COVID-related spending found evidence of corruption and improper use of funds, a finding that led to arrests.

ASJ’s growth was fueled by both international recognition and international donors. In 2012, ASJ was formally accredited as an official chapter of Transparency International, becoming a local representative of the global anti-corruption organization. By 2019, it had been recognized for its model of change by global initiatives such as the Paris Peace Forum and the World Justice Challenge. Meanwhile, its sister organization, ASJ-US, was established to spearhead fundraising efforts for the Honduras-based organization. For the 2024 fiscal year, ASJ-US raised over $2 million in support and revenue, and the work of ASJ-Honduras is also funded by 20 other government agencies and foundations. Today, ASJ-Honduras has roughly 60 employees, including researchers, lawyers, therapists and communications professionals.

Though methodical, the ASJ approach is also rooted in the communities it hopes to transform. Psychologist Maria Estella Núñez, who worked on ASJ’s violence prevention program from 2016-2022, spent years mentoring vulnerable youths and teaching families to handle conflict safely and productively.

“They’re not just giving them what they actually need, but they’re also strengthening their capacities at a community level,” said Núñez, who spoke with RNS via an interpreter. “They get to know their rights, but they can also do something about trying to get the authorities to comply with their rights. And once they have this type of knowledge, they can be more empowered, and they can be a more cohesive community.”

Despite ASJ’s success, Halperin’s book on the nonprofit suggests justice can’t be understood as part of a good vs. evil dichotomy. ASJ leaders had to weigh the risks of partnering with local vigilantes and flawed government leaders, and face the ethical implications of locking up teen gang members in inhumane and often deadly prisons. The complexity of justice also means it isn’t always guaranteed.

That was the case for the family of Dineyla Erazo. Raised in a Christian household in Honduras, Erazo told RNS her family was living in a small town near Tegucigalpa in 2014 when her father, a mechanic, refused to be extorted by local gang members.

“He went to the authorities, presented the complaint, did everything that you’re supposed to do,” said Erazo. “But unfortunately, since he refused to pay the extortion, he was murdered in his own shop.”

After that, Erazo’s family didn’t trust the police. ASJ took up her father’s case, attempting to track down who was responsible while providing the family with psychological assistance. The murderers were never caught.

“We didn’t get justice in a way that we would hope for,” Erazo observed. But, she added, “Just having an organization, the psychologists, helping us go through that process that was like very sudden, very heartbreaking and tragic, to navigate through the whole legal system, was something that we really appreciated.” A decade later, Erazo is ASJ’s deputy director of programs, overseeing fundraising proposals and evaluating ASJ projects.

Undergirding ASJ’s approach is the conviction that justice goes beyond charity and development work to tackle the structural barriers preventing communities from thriving. In recent years, that understanding has inspired nonprofit leaders in the U.S., including Kids First Chicago Executive Director Daniel Anello.

“We have the same way of using research and data to elevate real issues that people are encountering, and wedding numbers with narratives to really compel change,” said Anello. His nonprofit equips parents with data and empowers them to influence decision-makers in the Chicago Public School system. During the 2017-2018 school year, Kids First Chicago conducted focus groups with parents to evaluate a new universal enrollment application for Chicago high schools, advocating for improvements that impacted thousands of families systemwide. In 2020, the nonprofit researched student internet access and led a coalition that advocated for free, in-home internet for over 100,000 Chicago students, paid for by philanthropists and the city of Chicago.

“My first thought about ASJ was, how are they driving this change at scale? They’re seeing governance change. They’re impacting the entire police force,” said Anello, who invited Ver Beek to speak to his nonprofit board.

As the Chicago Public School system begins electing its school board members, Anello hopes Kids First Chicago can broaden the reach of its grassroots-driven research, even in a political context.

Hamernick is also taking cues from ASJ’s model. He believes their four-part strategy could reduce Chicago’s struggles with gun violence, corruption and financial bankruptcy. At the core of these issues, he says, is Chicago’s lack of a city charter — so, for the last six months, he’s been building a new alliance with former officials, clergy, community leaders and foundation heads to call for a charter.

“If you get systems change right, and I think ASJ is one of the few places in the world where you really see that, the benefit to the society is just immeasurably greater,” said Hamernick.

Hamernick has named the alliance A More Just Chicago.

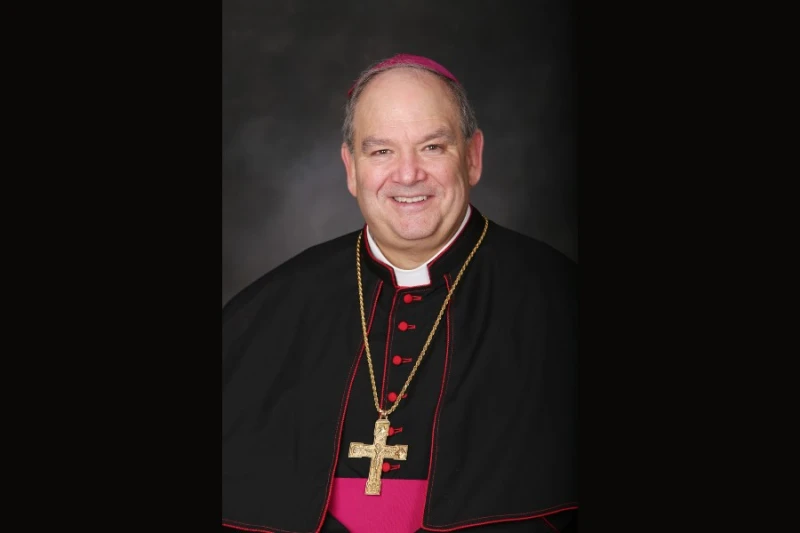

Archbishop Bernard Hebda of St. Paul-Minneapolis. / Credit: Archdiocese of St. Paul-Minneapolis

Archbishop Bernard Hebda of St. Paul-Minneapolis. / Credit: Archdiocese of St. Paul-Minneapolis

Washington, D.C. Newsroom, Aug 27, 2025 / 16:57 pm (CNA).

Archbishop Bernard Hebda, who leads the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, released a statement following the deadly shooting that took place on Wednesday morning at Annunciation Catholic School in southern Minneapolis.

“My heart is broken as I think about students, teachers, clergy and parishioners and the horror they witnessed in a church, a place where we should feel safe,” Hebda wrote in a statement Wednesday afternoon, hours after police confirmed two children were killed and 17 injured in the shooting.

Hebda expressed gratitude to Pope Leo XIV, who sent his condolences to Hebda after the attack, and all those around the world who have offered prayers following the shooting that occurred during a Mass for the K–8 school early Wednesday morning.

“I beg for the continued prayers of all of the priests and faithful of this archdiocese, as well for the prayers of all men and women of goodwill,” Hebda continued, “that the healing that only God can bring will be poured out on all those who were present at this morning’s Mass and particularly for the affected families who are only now beginning to comprehend the trauma they sustained.”

The Twin Cities archbishop further pledged the souls of the two children who lost their lives to God through the intercession of Our Lady, Queen of Peace, and called for an end to gun violence, which he described as “far too commonplace.”

He noted the Annunciation School shooting comes just 24 hours after another shooting near Cristo Rey Jesuit High School that reportedly left one dead and six injured on Tuesday.

“Our community is rightfully outraged at such horrific acts of violence perpetrated against the vulnerable and innocent,” Hebda wrote. “While we need to commit to working to prevent the recurrence of such tragedies, we also need to remind ourselves that we have a God of peace and of love, and that it is his love that we will need most as we strive to embrace those who are hurting so deeply.”

Hebda revealed that archdiocesan staff are currently working with the parish and school to “make sure they have the support and resources they need at this time and beyond.”

A prayer service is set to take place at 7 p.m. CT at the Academy of the Holy Angels in Richfield, Minnesota.

We have to be men and women of hope,” Hebda also said at a press conference on Wednesday afternoon. While he was speaking, a church bell rang in the background.

“A bell in the Catholic Church is always a call to prayer,” he continued, adding: “And we have to recognize that it’s through prayer … that we can indeed make a difference. That has to be the source of our hope.”

FBI Director Kash Patel announced in a social media post Wednesday afternoon that the FBI is investigating the shooting “as an act of domestic terrorism and hate crime targeting Catholics.” He also confirmed the identity of the shooter as Robin Westman, a trans-identifying male born as Robert Westman.

Updates on the shooting in Minneapolis, Minnesota:

— FBI Director Kash Patel (@FBIDirectorKash) August 27, 2025

The FBI is investigating this shooting as an act of domestic terrorism and hate crime targeting Catholics.

There were 2 fatalities, an 8-year-old and a 10-year-old. In addition, 14 children and 3 adults were injured.

The… https://t.co/ErFZpSieKS

U.S. President Donald Trump ordered American flags at the White House, across the country, and at all U.S. embassies, legations, consular offices, and other facilities abroad to be flown at half staff until sunset on Aug. 31 “as a mark of respect for the victims” of the deadly shooting.

President Donald J. Trump orders all flags of the United States shall be flown at half-staff at the White House and upon all public buildings and grounds as a mark of respect for the victims of the senseless acts of violence perpetrated on August 27 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. pic.twitter.com/S9Q18udIwO

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) August 27, 2025