(RNS) — A few humanitarians have become household names: Mother Teresa, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Mahatma Gandhi.

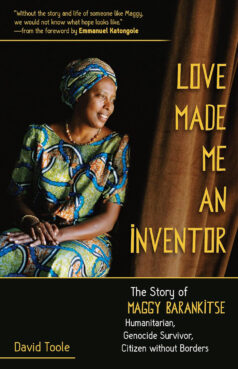

Maggy Barankitse is another — not nearly as well known, but driven by fighting injustice and a theological vision to make the world a better place.

Barankitse, who is now 69 and living in exile in Rwanda, is a native of neighboring Burundi, a small country to the south. It too has been wracked by internecine violence between Hutus and Tutsis, including lesser-known genocides that have killed tens of thousands of people. Barankitse lived through two of them and has dedicated her life to helping orphaned children — and later Burundian refugees in Rwanda — overcome their experiences.

David Toole, director of Duke University’s Kenan Institute for Ethics, has now written what he calls a portrait — not quite a full-fledged biography — of Barankitse. Called “Love Made Me an Inventor: The Story of Maggy Barankitse, Humanitarian, Genocide Survivor and Citizen Without Borders,” it is, at the heart, a story of their friendship.

In the book, released May 30, he describes Barankitse’s vision for Maison Shalom, a sprawling nonprofit that cared for thousands of orphaned children, both Hutu and Tutsi in Burundi. Later, after she’s forced to flee Burundi, she created its Rwandan counterpart, which grew out of the Mahama Refugee Camp that she established in 2015 to host refugees, primarily from Burundi. The camp, which has housed upward of 60,000 people, has become a model of refugee management.

RNS spoke with Toole about Barankitse, how she has transformed tragedy into hope and her belief in the power of love to change the world. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You talk in the book about how you met Maggy at a conference that Duke organized in Africa. What sparked your interest in writing a book on her?

It was a conference in Burundi in 2009, organized by Duke’s Center for Reconciliation. Maggy showed up. Nobody had heard of her. She had a half an hour in front of 70 people, mostly East Africans, and she told her story. Once you meet Maggy, you’re immediately captured, but she’d invited us to travel with her to Ruyigi, her hometown, a three- or four-hour drive on bad roads. A small group of us went on the weekend. She showed us her work, which included the swimming pool and movie theater she’d built in the middle of the war for the children so that they weren’t just being clothed and fed, but also given dignity. The place included vocational training centers, a library, a restaurant, organic farm and, pointedly, a brand-new hospital.

It was the tour of the hospital that probably was the thing that compelled me to pursue the story. The hospital was sitting on top of what had been her family village that was destroyed in the opening days of the civil war in 1993. As we walked around the complex, we came upon this large structure which was the morgue. It was large enough to accommodate six families caring for the bodies and preparing for burial. This was the building that Maggy was most proud of.

All of that added up and started sticking in my mind for months, and compelled me to want to know more. I had an incredible drive to satisfy my curiosity: How could she have done all these remarkable things following such traumatic things? It was probably five years before I actually wrote anything about her.

Maggy is a devout Catholic, but she’s not a nun. Neither is she married or partnered. By the age of 30, she’s a single mother with seven adopted children. How did she develop this unconventional sense of her vocation?

The immense trauma, out of which she then started to do these amazing things for the next few decades, happened in 1993. But in 1972, she was a 16-year-old high school student when there was a genocide in Burundi, unknown to the rest of the world. It led to the death of probably a quarter-million, mostly Hutus at the hands of Tutsis. Maggy’s family is Tutsi, and she had a very devout Catholic mother who taught her from the time she was small that we’re all one human family. And so when Maggy goes to school and realizes some of her Hutu teachers are missing because they’ve been killed in the genocide, and some of her Hutu classmates no longer have fathers because they’ve been killed in the genocide, and the Catholic school was saying nothing about what was happening, she flees the school, runs back to her mother and says, “You lied to me because you told me that we’re all one human family and now I see that’s not true. I won’t go back to that school.” That’s the beginning of a vocation.

There was a deep sense she had from a very young age that her job in the world was to care for people in need. It’s almost as if she was built this way — to act out against an injustice anytime she saw one. She went to a different school to train to be a teacher where she could actually work against the division between Hutus and Tutsis. Her goal was to teach that this division was not something that existed in reality, but she was fired from her teaching job because she took on the government. And then in the midst of all that, she becomes a young mother of adopted children. Being single and adopting children just became the way she did it. She was adopting Hutu and Tutsi children, which in some way probably explains the difficulty of marriage because it would have been very hard to marry a Tutsi man who would have allowed you to have Hutu children and vice versa.

The next thing you know, the mother part of that became just an amazingly expansive thing. The numbers really did pile up into the tens of thousands of children that she worked with through Maison Shalom.

Maggy has incredible self-confidence and a kind of spunkiness and audacity. Where does that come from?

In some ways, I think this is the mystery of it all. She steals the bishop’s curtains to sew clothes for children (in the orphanage) because she asked the bishop for clothes for children, and he said no. There’s something about her imagination that works this way. When she’s confronted with an obstacle, she just refuses to see it as insurmountable.

The other example, there’s a UNICEF conference on children in distress and all of these NGOs come through with their PowerPoint slides, wanting cars and computers and offices and all of the things to make their world work financially. She’s disgusted by this. Next thing you know, she’s pulling children in off the street and bringing them into the buffet in the conference hallway, telling them to eat the food all these other people are supposed to eat. It’s like this spontaneous perfect response that just comes to her because she opens her mind to what the possibilities might be. It’s a deeply theological imagination that gives you that kind of sight: Let me counteract this horrible thing that happened there with the most loving thing I could think of. So you get a hospital where the destroyed village used to be. You get the swimming pool where a mass grave used to be. She just does it over and over again, but exactly where it comes from is kind of a mystery.

She seems to have developed this moral imagination very early on. Did it all come from her mother and the church?

From a very young age, her mother took her to Mass every day before school and often took her to the prisons after Mass. Maggy calls it a second Mass where they would go feed the prisoners. She sort of got her theology by example. One of the bishops who later became an archbishop in Burundi did send her away for religious education in France for a couple of years with the idea that when she came back to Burundi, she would become a teacher charged with religious education. She’s constantly drawing on biblical narratives and placing her own life in the context of biblical narrative. It’s as if what’s happening in the Bible is happening now.

A lot of people are talking about genocide these days. Is there anything Maggy says that can help us grapple with that?

She lived in a country divided between Hutu and Tutsi ethnic realities leading to genocide, with the first big genocide in Burundi in 1972. So Maggy grew up in a country where so-called polarization was literally leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. These are deep, deep divisions that Maggy looked at and said, these are just fictions. Her whole life has really been trying to create a world where those divisions don’t exist. The tens of thousands of children who went through Maison Shalom, they really are not letting Hutu-Tutsi be the drivers of their life.

She also is incredibly eloquent in a simple way. One of her favorite words is “stupid.” When I ask her what she would dream of doing, she says, I dream of standing in front of the U.N. and telling all of the representatives how stupid they are. She definitely wants to try to show us that all of the things that we get caught up in — a grab for power, our hubris — is just simply stupid, a mistake and has nothing to do with what it really means to be human. It’s deeply theological.

The Christian Century published one of her sayings as their quote of the week: “I grew up in a family that taught me to be a builder of hope, of new community, of humanity. We must shine in this life. It’s the only mission we have on Earth. When God created us, he said, ‘Go and make this Earth into paradise.’ It‘s not so difficult. We just don’t realize that we have an exceptional, amazing vocation.”

If we could just remind ourselves of that, the world would be a different place.

Original Source: