(RNS) — There was something mythological about Bob Weir — utterly timeless and almost primeval. An American original troubadour telling stories that felt older than the nation itself, he somehow oriented toward a future just beyond our reach.

You could imagine a world before him, but a world after him was unfathomable. Which is why it landed with such force and sadness to learn that Weir died over the weekend at age 78.

His story begins like a folk tale. A teenage kid, forever known as “Bobby,” wanders the storefronts of Palo Alto, California, on New Year’s Eve, 1963. He hears banjo music drifting from somewhere nearby — familiar yet mysterious, close enough to follow. Something in that sound feels like truth, or at least a trail toward it.

Palo Alto at the time was still a place of apricot orchards and suburban promise, not yet the global nerve center of big tech and artificial intelligence. Bobby follows the music down an alley and meets a fellow traveler: a young man named Jerry Garcia. Instruments come out. A jam begins. And in that unplanned encounter, something new is born that somehow feels both ancient and modern all at once.

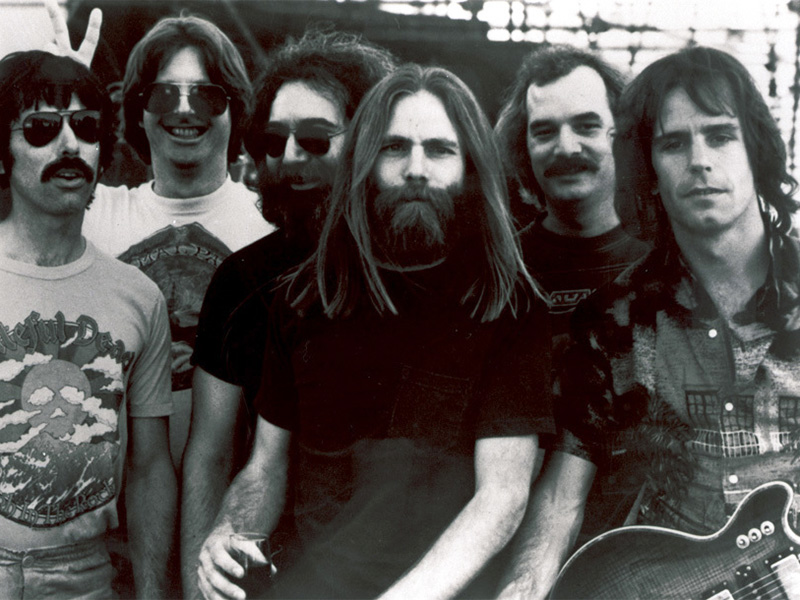

Within two years, that jam would become the Grateful Dead.

For the next three decades, Weir and Garcia — alongside Phil Lesh, Mickey Hart, Bill Kreutzmann and a widening circle of collaborators — led not just a band but a community on a shared quest. Dead shows were less performances than gatherings: temporary villages where strangers became companions through sound, attention and improvisation. That era came to a shuddering halt in 1995, when Garcia died just weeks after the band’s final concert at Soldier Field in Chicago. For many, it felt as though the music itself had stopped.

But Weir kept following the thread.

With his longtime songwriting partner, John Perry Barlow, he had already given us the assurance that proved true: the music never stopped. Over the next 30 years, Weir carried the songs forward with old friends and new ones, as if they contained some durable wisdom about how to be human together. We glimpsed that wisdom again last year in Dead & Company’s final run at the Sphere in Las Vegas, and again at the Grateful Dead’s 60th anniversary shows in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park — moments that felt less like nostalgia than inheritance.

Weir was never religious in any conventional sense. After all, one of his most enduring characters was the faux-messianic huckster of Estimated Prophet. But there was a deep, abiding spirituality to his work. He sang old folk songs and stretched them into psychedelic exploration. He carried forward cowboy ballads from a long-lost West. He dropped jazz standards like “Milestones” into the middle of sprawling sets. All of it served a single impulse: follow the music wherever it leads and bring people with you.

No song captured that ethos more fully than “Playing in the Band.” It arrives like a sunrise, promising “daybreak on the land,” and opens not with certainty but invitation. On the original 1972 studio recording, Donna Jean Godchaux’s harmonies rise into the mix — just a year after she had been in the audience, wishing she might someday join the band. The song lifts off into a cosmic swirl of guitars, keys and drums. It is radically inclusive. You do not listen so much as enter. No one comes back unchanged.

In one of his final interviews, with Rolling Stone just a year ago, Weir reflected not only on his life but on the state of the country. Troubled by Donald Trump’s return, renewed political cruelty and division, he returned to the truth he had learned onstage again and again: “I have a feeling that it’s music that’s going to bring this country together. Nothing else is going to work.”

The Dead were never partisan. Their audience has always spanned the political spectrum — Democrats, Republicans, libertarians, Greens and those allergic to labels altogether. Still, Weir was not disengaged. He spoke out on climate change, gun violence and health. Recent tours partnered with HeadCount, registering voters between sets. This was not ideology; it was participation.

I wasn’t ready to say goodbye to Bob Weir. The year ahead already feels mythological in its own foreboding way. I wanted one more night in the desert with our white-bearded sage in a Stetson, inviting us into something better. I wanted to raise my fist to “Throwing Stones” one more time, naming hard truths without surrendering hope. I wanted another “My Brother Esau,” shadowboxing the apocalypse and wandering the land.

Near the end of that Rolling Stone interview, Weir said he hoped to be remembered for bringing cultures together — “by virtue or by example” — so that people of different persuasions might find something they could agree on in the music, and find each other through it.

There’s an old Dead saying: Weir everywhere. It works as a bumper sticker. But it works even better as a totem — an invitation to join in despite our differences, to listen, to stay and to make something larger than ourselves. In that sense, and in that practice, the music never stops.

(Adam Nicholas Phillips is the CEO of Interfaith America. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Original Source: